Linux non è Windows

oggi girando per la rete mi sono imbattuto in un testo che contiene una serie di riflessioni comuni sull’annoso problema di reciproca comprensione tra chi usa Linux e chi ci vorrebbe passare, o si sente ripetere “passa a Linux” e non sa cosa sta scegliendo realmente.

oggi girando per la rete mi sono imbattuto in un testo che contiene una serie di riflessioni comuni sull’annoso problema di reciproca comprensione tra chi usa Linux e chi ci vorrebbe passare, o si sente ripetere “passa a Linux” e non sa cosa sta scegliendo realmente.

Vi propongo il link all’originale e anche ad una traduzione in italiano.

Ottobre 4th, 2009 at 3:57 pm

inglese e italiano in caso i link si rompessero un domani.

In the following article, I refer to the GNU/Linux OS and various Free & Open-Source Software (FOSS) projects under the catch-all name of “Linux”. It scans better.

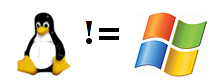

Linux != Windows

(Linux is Not Windows)

Derived works

If you’ve been pointed at this page, then the chances are you’re a relatively new Linux user who’s having some problems making the switch from Windows to Linux. This causes many problems for many people, hence this article was written. Many individual issues arise from this single problem, so the page is broken down into multiple problem areas.

Problem #1: Linux isn’t exactly the same as Windows.

You’d be amazed how many people make this complaint. They come to Linux, expecting to find essentially a free, open-source version of Windows. Quite often, this is what they’ve been told to expect by over-zealous Linux users. However, it’s a paradoxical hope.

The specific reasons why people try Linux vary wildly, but the overall reason boils down to one thing: They hope Linux will be better than Windows. Common yardsticks for measuring success are cost, choice, performance, and security. There are many others. But every Windows user who tries Linux, does so because they hope it will be better than what they’ve got.

Therein lies the problem.

It is logically impossible for any thing to be better than any other thing whilst remaining completely identical to it. A perfect copy may be equal, but it can never surpass. So when you gave Linux a try in hopes that it would be better, you were inescapably hoping that it would be different. Too many people ignore this fact, and hold up every difference between the two OSes as a Linux failure.

As a simple example, consider driver upgrades: one typically upgrades a hardware driver on Windows by going to the manufacturer’s website and downloading the new driver; whereas in Linux you upgrade the kernel.

This means that a single Linux download & upgrade will give you the newest drivers available for your machine, whereas in Windows you would have to surf to multiple sites and download all the upgrades individually. It’s a very different process, but it’s certainly not a bad one. But many people complain because it’s not what they’re used to.

Or, as an example you’re more likely to relate to, consider Firefox: One of the biggest open-source success stories. A web browser that took the world by storm. Did it achieve this success by being a perfect imitation of IE, the then-most-popular browser?

No. It was successful because it was better than IE, and it was better because it was different. It had tabbed browsing, live bookmarks, built-in searchbar, PNG support, adblock extensions, and other wonderful things. The “Find” functionality appeared in a toolbar at the bottom and looked for matches as you typed, turning red when you had no match. IE had no tabs, no RSS functionality, searchbars only via third-party extensions, and a find dialogue that required a click on “OK” to start looking and a click on “OK” to clear the “Not found” error message. A clear and inarguable demonstration of an open-source application achieving success by being better, and being better by being different. Had FF been an IE clone, it would have vanished into obscurity. And had Linux been a Windows clone, the same would have happened.

So the solution to problem #1: Remember that where Linux is familiar and the same as what you’re used to, it isn’t new & improved. Welcome the places where things are different, because only here does it have a chance to shine.

Problem #2: Linux is too different from Windows

The next issue arises when people do expect Linux to be different, but find that some differences are just too radical for their liking. Probably the biggest example of this is the sheer amount of choice available to Linux users. Whereas an out-of-the-box-Windows user has the Classic or XP desktop with Wordpad, Internet Explorer, and Outlook Express installed, an out-of-the-box-Linux user has hundreds of distros to choose from, then Gnome or KDE or Fluxbox or whatever, with vi or emacs or kate, Konqueror or Opera or Firefox or Mozilla, and so on and so forth.

A Windows user isn’t used to making so many choices just to get up & running. Exasperated “Does there have to be so much choice?” posts are very common.

Does Linux really have to be so different from Windows? After all, they’re both operating systems. They both do the same job: Power your computer & give you something to run applications on. Surely they should be more or less identical?

Look at it this way: Step outside and take a look at all the different vehicles driving along the road. These are all vehicles designed with more or less the same purpose: To get you from A to B via the roads. Note the variety in designs.

But, you may be thinking, car differences are really quite minor: they all have a steering wheel, foot-pedal controls, a gear stick, a handbrake, windows & doors, a petrol tank. . . If you can drive one car, you can drive any car!

Quite true. But did you not see that some people weren’t driving cars, but were riding motorbikes instead. . ?

Switching from one version of Windows to another is like switching from one car to another. Win95 to Win98, I honestly couldn’t tell the difference. Win98 to WinXP, it was a bigger change but really nothing major.

But switching from Windows to Linux is like switching from a car to a motorbike. They may both be OSes/road vehicles. They may both use the same hardware/roads. They may both provide an environment for you to run applications/transport you from A to B. But they use fundamentally different approaches to do so.

Windows/cars are not safe from viruses/theft unless you install an antivirus/lock the doors. Linux/motorbikes don’t have viruses/doors, so are perfectly safe without you having to install an antivirus/lock any doors.

Or look at it the other way round:

Linux/cars were designed from the ground up for multiple users/passengers. Windows/motorbikes were designed for one user/passenger. Every Windows user/motorbike driver is used to being in full control of his computer/vehicle at all times. A Linux user/car passenger is used to only being in control of his computer/vehicle when logged in as root/sitting in the driver’s seat.

Two different approaches to fulfilling the same goal. They differ in fundamental ways. They have different strengths and weaknesses: A car is the clear winner at transporting a family & a lot of cargo from A to B: More seats & more storage space. A motorbike is the clear winner at getting one person from A to B: Less affected by congestion and uses less fuel.

There are many things that don’t change when you switch between cars and motorbikes: You still have to put petrol in the tank, you still have to drive on the same roads, you still have to obey the traffic lights and Stop signs, you still have to indicate before turning, you still have to obey the same speed limits.

But there are also many things that do change: Car drivers don’t have to wear crash helmets, motorbike drivers don’t have to put on a seatbelt. Car drivers have to turn the steering wheel to get around a corner, motorbike drivers have to lean over. Car drivers accelerate by pushing a foot-pedal, motorbike drivers accelerate by twisting a hand control.

A motorbike driver who tries to corner a car by leaning over is going to run into problems very quickly. And Windows users who try to use their existing skills and habits generally also find themselves having many issues. In fact, Windows “Power Users” frequently have more problems with Linux than people with little or no computer experience, for this very reason. Typically, the most vehement “Linux is not ready for the desktop yet” arguments come from ingrained Windows users who reason that if they couldn’t make the switch, a less-experienced user has no chance. But this is the exact opposite of the truth.

So, to avoid problem #2: Don’t assume that being a knowledgeable Windows user means you’re a knowledgeable Linux user: When you first start with Linux, you are a novice.

Problem #3: Culture shock

Subproblem #3a: There is a culture

Windows users are more or less in a customer-supplier relationship: They pay for software, for warranties, for support, and so on. They expect software to have a certain level of usability. They are therefore used to having rights with their software: They have paid for technical support and have every right to demand that they receive it. They are also used to dealing with entities rather than people: Their contracts are with a company, not with a person.

Linux users are in more of a community. They don’t have to buy the software, they don’t have to pay for technical support. They download software for free & use Instant Messaging and web-based forums to get help. They deal with people, not corporations.

A Windows user will not endear himself by bringing his habitual attitudes over to Linux, to put it mildly.

The biggest cause of friction tends to be in the online interactions: A “3a” user new to Linux asks for help with a problem he’s having. When he doesn’t get that help at what he considers an acceptable rate, he starts complaining and demanding more help. Because that’s what he’s used to doing with paid-for tech support. The problem is that this isn’t paid-for support. This is a bunch of volunteers who are willing to help people with problems out of the goodness of their hearts. The new user has no right to demand anything from them, any more than somebody collecting for charity can demand larger donations from contributors.

In much the same way, a Windows user is used to using commercial software. Companies don’t release software until it’s reliable, functional, and user-friendly enough. So this is what a Windows user tends to expect from software: It starts at version 1.0. Linux software, however, tends to get released almost as soon as it’s written: It starts at version 0.1. This way, people who really need the functionality can get it ASAP; interested developers can get involved in helping improve the code; and the community as a whole stays aware of what’s going on.

If a “3a” user runs into trouble with Linux, he’ll complain: The software hasn’t met his standards, and he thinks he has a right to expect that standard. His mood won’t be improved when he gets sarcastic replies like “I’d demand a refund if I were you”

So, to avoid problem #3a: Simply remember that you haven’t paid the developer who wrote the software or the people online who provide the tech support. They don’t owe you anything.

Subproblem #3b: New vs. Old

Linux pretty much started out life as a hacker’s hobby. It grew as it attracted more hobbyist hackers. It was quite some time before anybody but a geek stood a chance of getting a useable Linux installation working easily. Linux started out “By geeks, for geeks.” And even today, the majority of established Linux users are self-confessed geeks.

And that’s a pretty good thing: If you’ve got a problem with hardware or software, having a large number of geeks available to work on the solution is a definite plus.

But Linux has grown up quite a bit since its early days. There are distros that almost anybody can install, even distros that live on CDs and detect all your hardware for you without any intervention. It’s become attractive to non-hobbyist users who are just interested in it because it’s virus-free and cheap to upgrade. It’s not uncommon for there to be friction between the two camps. It’s important to bear in mind, however, that there’s no real malice on either side: It’s lack of understanding that causes the problems.

Firstly, you get the hard-core geeks who still assume that everybody using Linux is a fellow geek. This means they expect a high level of knowledge, and often leads to accusations of arrogance, elitism, and rudeness. And in truth, sometimes that’s what it is. But quite often, it’s not: It’s elitist to say “Everybody ought to know this”. It’s not elitist to say “Everybody knows this” – quite the opposite.

Secondly, you get the new users who’re trying to make the switch after a lifetime of using commercial OSes. These users are used to software that anybody can sit down & use, out-of-the-box.

The issues arise because group 1 is made up of people who enjoy being able to tear their OS apart and rebuild it the way they like it, while group 2 tends to be indifferent to the way the OS works, so long as it does work.

A parallel situation that can emphasize the problems is Lego. Picture the following:

New: I wanted a new toy car, and everybody’s raving about how great Lego cars can be. So I bought some Lego, but when I got home, I just had a load of bricks and cogs and stuff in the box. Where’s my car??

Old: You have to build the car out of the bricks. That’s the whole point of Lego.

New: What?? I don’t know how to build a car. I’m not a mechanic. How am I supposed to know how to put it all together??

Old: There’s a leaflet that came in the box. It tells you exactly how to put the bricks together to get a toy car. You don’t need to know how, you just need to follow the instructions.

New: Okay, I found the instructions. It’s going to take me hours! Why can’t they just sell it as a toy car, instead of making you have to build it??

Old: Because not everybody wants to make a toy car with Lego. It can be made into anything we like. That’s the whole point.

New: I still don’t see why they can’t supply it as a car so people who want a car have got one, and other people can take it apart if they want to. Anyway, I finally got it put together, but some bits come off occasionally. What do I do about this? Can I glue it?

Old: It’s Lego. It’s designed to come apart. That’s the whole point.

New: But I don’t want it to come apart. I just want a toy car!

Old: Then why on Earth did you buy a box of Lego??

It’s clear to just about anybody that Lego is not really aimed at people who just want a toy car. You don’t get conversations like the above in real life. The whole point of Lego is that you have fun building it and you can make anything you like with it. If you’ve no interest in building anything, Lego’s not for you. This is quite obvious.

As far as the long-time Linux user is concerned, the same holds true for Linux: It’s an open-source, fully-customizeable set of software. That’s the whole point. If you don’t want to hack the components a bit, why bother to use it?

But there’s been a lot of effort lately to make Linux more suitable for the non-hackers, a situation that’s not a million miles away from selling pre-assembled Lego kits, in order to make it appeal to a wider audience. Hence you get conversations that aren’t far away from the ones above: Newcomers complain about the existence of what the established users consider to be fundamental features, and resent having the read a manual to get something working. But complaining that there are too many distros; or that software has too many configuration options; or that it doesn’t work perfectly out-of-the-box; is like complaining that Lego can be made into too many models, and not liking the fact that it can be broken down into bricks and built into many other things.

So, to avoid problem #3b: Just remember that what Linux seems to be now is not what Linux was in the past. The largest and most necessary part of the Linux community, the hackers and the developers, like Linux because they can fit it together the way they like; they don’t like it in spite of having to do all the assembly before they can use it.

Problem #4: Designed for the designer

In the car industry, you’ll very rarely find that the person who designed the engine also designed the car interior: It calls for totally different skills. Nobody wants an engine that only looks like it can go fast, and nobody wants an interior that works superbly but is cramped and ugly. And in the same way, in the software industry, the user interface (UI) is not usually created by the people who wrote the software.

In the Linux world, however, this is not so much the case: Projects frequently start out as one man’s toy. He does everything himself, and therefore the interface has no need of any kind of “user friendly” features: The user knows everything there is to know about the software, he doesn’t need help. Vi is a good example of software deliberately created for a user who already knows how it works: It’s not unheard of for new users to reboot their computers because they couldn’t figure out how else to get out of vi.

However, there is an important difference between a FOSS programmer and most commercial software writers: The software a FOSS programmer creates is software that he intends to use. So whilst the end result might not be as ‘comfortable’ for the novice user, they can draw some comfort in knowing that the software is designed by somebody who knows what the end-users needs are: He too is an end-user. This is very different from commercial software writers, who are making software for other people to use: They are not knowledgeable end-users.

So whilst vi has an interface that is hideously unfriendly to new users, it is still in use today because it is such a superb interface once you know how it works. Firefox was created by people who regularly browse the Web. The Gimp was built by people who use it to manipulate graphics files. And so on.

So Linux interfaces are frequently a bit of a minefield for the novice: Despite its popularity, vi should never be considered by a new user who just wants to quickly make a few changes to a file. And if you’re using software early in its lifecycle, a polished, user-friendly interface is something you’re likely to find only in the “ToDo” list: Functionality comes first. Nobody designs a killer interface and then tries to add functionality bit by bit. They create functionality, and then improve the interface bit by bit.

So to avoid #4 issues: Look for software that’s specifically aimed at being easy for new users to use, or accept that some software that has a steeper learning curve than you’re used to. To complain that vi isn’t friendly enough for new users is to be laughed at for missing the point.

Problem #5: The myth of “user-friendly”

This is a big one. It’s a very big term in the computing world, “user-friendly”. It’s even the name of a particularly good webcomic. But it’s a bad term.

The basic concept is good: That software be designed with the needs of the user in mind. But it’s always addressed as a single concept, which it isn’t.

If you spend your entire life processing text files, your ideal software will be fast and powerful, enabling you to do the maximum amount of work for the minimum amount of effort. Simple keyboard shortcuts and mouseless operation will be of vital importance.

But if you very rarely edit text files, and you just want to write an occasional letter, the last thing you want is to struggle with learning keyboard shortcuts. Well-organized menus and clear icons in toolbars will be your ideal.

Clearly, software designed around the needs of the first user will not be suitable for the second, and vice versa. So how can any software be called “user-friendly”, if we all have different needs?

The simple answer: User-friendly is a misnomer, and one that makes a complex situation seem simple.

What does “user-friendly” really mean? Well, in the context in which it is used, “user friendly” software means “Software that can be used to a reasonable level of competence by a user with no previous experience of the software.” This has the unfortunate effect of making lousy-but-familiar interfaces fall into the category of “user-friendly”.

Subproblem #5a: Familiar is friendly

So it is that in most “user-friendly” text editors & word processors, you Cut and Paste by using Ctrl-X and Ctrl-V. Totally unintuitive, but everybody’s used to these combinations, so they count as a “friendly” combination.

So when somebody comes to vi and finds that it’s “d” to cut, and “p” to paste, it’s not considered friendly: It’s not what anybody is used to.

Is it superior? Well, actually, yes.

With the Ctrl-X approach, how do you cut a word from the document you’re currently in? (No using the mouse!)

From the start of the word, Ctrl-Shift-Right to select the word.

Then Ctrl-X to cut it.

The vi approach? dw deletes the word.

How about cutting five words with a Ctrl-X application?

From the start of the words, Ctrl-Shift-Right

Ctrl-Shift-Right

Ctrl-Shift-Right

Ctrl-Shift-Right

Ctrl-Shift-Right

Ctrl-X

And with vi?

d5w

The vi approach is far more versatile and actually more intuitive: “X” and “V” are not obvious or memorable “Cut” and “Paste” commands, whereas “dw” to delete a word, and “p” to put it back is perfectly straightforward. But “X” and “V” are what we all know, so whilst vi is clearly superior, it’s unfamiliar. Ergo, it is considered unfriendly. On no other basis, pure familiarity makes a Windows-like interface seem friendly. And as we learned in problem #1, Linux is necessarily different to Windows. Inescapably, Linux always appears less “user-friendly” than Windows.

To avoid #5a problems, all you can really do is try and remember that “user-friendly” doesn’t mean “What I’m used to”: Try doing things your usual way, and if it doesn’t work, try and work out what a total novice would do.

Subproblem #5b: Inefficient is friendly

This is a sad but inescapable fact. Paradoxically, the harder you make it to access an application’s functionality, the friendlier it can seem to be.

This is because friendliness is added to an interface by using simple, visible ‘clues’ – the more, the better. After all, if a complete novice to computers is put in front of a WYSIWYG word processor and asked to make a bit of text bold, which is more likely:

* He’ll guess that “Ctrl-B” is the usual standard

* He’ll look for clues, and try clicking on the “Edit” menu. Unsuccessful, he’ll try the next likely one along the row of menus: “Format”. The new menu has a “Font” option, which seems promising. And Hey! There’s our “Bold” option. Success!

Next time you do any processing, try doing every job via the menus: No shortcut keys, and no toolbar icons. Menus all the way. You’ll find you slow to a crawl, as every task suddenly demands a multitude of keystrokes/mouseclicks.

Making software “user-friendly” in this fashion is like putting training wheels on a bicycle: It lets you get up & running immediately, without any skill or experience needed. It’s perfect for a beginner. But nobody out there thinks that all bicycles should be sold with training wheels: If you were given such a bicycle today, I’ll wager the first thing you’d do is remove them for being unnecessary encumbrances: Once you know how to ride a bike, training wheels are unnecessary.

And in the same way, a great deal of Linux software is designed without “training wheels” – it’s designed for users who already have some basic skills in place. After all, nobody’s a permanent novice: Ignorance is short-lived, and knowledge is forever. So the software is designed with the majority in mind.

This might seem an excuse: After all, MS Word has all the friendly menus, and it has toolbar buttons, and it has shortcut keys. . . Best of all worlds, surely? Friendly and efficient.

However, this has to be put into perspective: Firstly, the practicalities: having menus and toolbars and shortcuts and all would mean a lot of coding, and it’s not like Linux developers all get paid for their time. Secondly, it still doesn’t really take into account serious power-users: Very few professional wordsmiths use MS Word. Ever meet a coder who used MS Word? Compare that to how many use emacs & vi.

Why is this? Firstly, because some “friendly” behaviour rules out efficient behaviour: See the “Cut&Copy” example above. And secondly, because most of Word’s functionality is buried in menus that you have to use: Only the most common functionality has those handy little buttons in toolbars at the top. The less-used functions that are still vital for serious users just take too long to access.

Something to bear in mind, however, is that “training wheels” are often available as “optional extras” for Linux software: They might not be obvious, but frequently they’re available.

Take mplayer. You use it to play a video file by typing mplayer filename in a terminal. You fastforward & rewind using the arrow keys and the PageUp & PageDown keys. This is not overly “user-friendly”. However, if you instead type gmplayer filename, you’ll get the graphical frontend, with all its nice, friendly , familiar buttons.

Take ripping a CD to MP3 (or Ogg): Using the command-line, you need to use cdparanoia to rip the files to disc. Then you need an encoder. . . It’s a hassle, even if you know exactly how to use the packages (imho). So download & install something like Grip. This is an easy-to-use graphical frontend that uses cdparanoia and encoders behind-the-scenes to make it really easy to rip CDs, and even has CDDB support to name the files automatically for you.

The same goes for ripping DVDs: The number of options to pass to transcode is a bit of a nightmare. But using dvd::rip to talk to transcode for you makes the whole thing a simple, GUI-based process which anybody can do.

So to avoid #5b issues: Remember that “training wheels” tend to be bolt-on extras in Linux, rather than being automatically supplied with the main product. And sometimes, “training wheels” just can’t be part of the design.

Problem #6: Imitation vs. Convergence

An argument people often make when they find that Linux isn’t the Windows clone they wanted is to insist that this is what Linux has been (or should have been) attempting to be since it was created, and that people who don’t recognise this and help to make Linux more Windows-like are in the wrong. They draw on many arguments for this:

Linux has gone from Command-Line- to Graphics-based interfaces, a clear attempt to copy Windows

Nice theory, but false: The original X windowing system was released in 1984, as the successor to the W windowing system ported to Unix in 1983. Windows 1.0 was released in 1985. Windows didn’t really make it big until version 3, released in 1990 – by which time, X windows had for years been at the X11 stage we use today. Linux itself was only started in 1991. So Linux didn’t create a GUI to copy Windows: It simply made use of a GUI that existed long before Windows.

Windows 3 gave way to Windows 95 – making a huge level of changes to the UI that Microsoft has never equalled since. It had many new & innovative features: Drag & drop functionality; taskbars, and so on. All of which have since been copied by Linux, of course.

Actually. . . no. All the above existed prior to Microsoft making use of them. NeXTSTeP in particular was a hugely advanced (for the time) GUI, and it predated Win95 significantly – version 1 released in 1989, and the final version in 1995.

Okay, okay, so Microsoft didn’t think up the individual features that we think of as the Windows Look-and-Feel. But it still created a Look-and-Feel, and Linux has been trying to imitate that ever since.

To debunk this, one must discuss the concept of convergent evolution. This is where two completely different and independent systems evolve over time to become very similar. It happens all the time in biology. For example, sharks and dolphins. Both are (typically) fish-eating marine organisms of about the same size. Both have dorsal fins, pectoral fins, tail fins, and similar, streamlined shapes.

However, sharks evolved from fish, while dolphins evolved from a land-based quadrupedal mammal of some sort. The reason they have very similar overall appearances is that they both evolved to be as efficient as possible at living within a marine environment. At no stage did pre-dolphins (the relative newcomers) look at sharks and think “Wow, look at those fins. They work really well. I’ll try and evolve some myself!”

Similarly, it’s perfectly true to look at early Linux desktops and see FVWM and TWM and a lot of other simplistic GUIs. And then look at modern Linux desktops, and see Gnome & KDE with their taskbars and menus and eye-candy. And yes, it’s true to say that they’re a lot more like Windows than they used to be.

But then, so is Windows: Windows 3.0 had no taskbar that I remember. And the Start menu? What Start menu?

Linux didn’t have a desktop anything like modern Windows. Microsoft didn’t either. Now they both do. What does this tell us?

It tells us that developers in both camps looked for ways of improving the GUI, and because there are only a limited number of solutions to a problem, they often used very similar methods. Similarity does not in any way prove or imply imitation. Remembering that will help you avoid straying into problem #6 territory.

Problem #7: That FOSS thing.

Oh, this causes problems. Not intrinsically: The software being free and open-source is a wonderful and immensely important part of the whole thing. But understanding just how different FOSS is from proprietary software can be too big an adjustment for some people to make.

I’ve already mentioned some instances of this: People thinking they can demand technical support and the like. But it goes far beyond that.

Microsoft’s Mission Statement is “A computer on every desktop” – with the unspoken rider that each computer should be running Windows. Microsoft and Apple both sell operating systems, and both do their utmost to make sure their products get used by the largest number of people: They’re businesses, out to make money.

And then there is FOSS. Which, even today, is almost entirely non-commercial.

Before you reach for your email client to tell me about Red Hat, Suse, Linspire and all: Yes, I know they “sell” Linux. I know they’d all love Linux to be adopted universally, especially their own flavour of it. But don’t confuse the suppliers with the manufacturers. The Linux kernel was not created by a company, and is not maintained by people out to make a profit with it. The GNU tools were not created by a company, and are not maintained by people out to make a profit with them. The X11 windowing system. . . well, the most popular implementation is xorg right now, and the “.org” part should tell you all you need to know. Desktop software: Well, you might be able to make a case for KDE being commercial, since it’s Qt-based. But Gnome, Fluxbox, Enlightenment, etc. are all non-profit. There are people out to sell Linux, but they are very much the minority.

Increasing the number of end-users of proprietary software leads to a direct financial benefit to the company that makes it. This is simply not the case for FOSS: There is no direct benefit to any FOSS developer in increasing the userbase. Indirect benefits, yes: Personal pride; an increased potential for finding bugs; more likelihood of attracting new developers; possibly a chance of a good job offer; and so on.

But Linus Torvalds doesn’t make money from increased Linux usage. Richard Stallman doesn’t get money from increased GNU usage. All those servers running OpenBSD and OpenSSH don’t put a penny into the OpenBSD project’s pockets. And so we come to the biggest problem of all when it comes to new users and Linux:

They find out they’re not wanted.

New users come to Linux after spending their lives using an OS where the end-user’s needs are paramount, and “user friendly” and “customer focus” are considered veritable Holy Grails. And they suddenly find themselves using an OS that still relies on ‘man’ files, the command-line, hand-edited configuration files, and Google. And when they complain, they don’t get coddled or promised better things: They get bluntly shown the door.

That’s an exaggeration, of course. But it is how a lot of potential Linux converts perceived things when they tried and failed to make the switch.

In an odd way, FOSS is actually a very selfish development method: People only work on what they want to work on, when they want to work on it. Most people don’t see any need to make Linux more attractive to inexperienced end-users: It already does what they want it to do, why should they care if it doesn’t work for other people?

FOSS has many parallels with the Internet itself: You don’t pay the writer of a webpage/the software to download and read/install it. Ubiquitous broadband/User-friendly interfaces are of no great interest to somebody who already has broadband/knows how to use the software. Bloggers/developers don’t need to have lots of readers/users to justify blogging/coding. There are lots of people making lots of money off it, but it’s not by the old-fashioned “I own this and you have to pay me if you want some of it” method that most businesses are so enamoured of; it’s by providing services like tech-support/e-commerce.

Linux is not interested in market share. Linux does not have customers. Linux does not have shareholders, or a responsibility to the bottom line. Linux was not created to make money. Linux does not have the goal of being the most popular and widespread OS on the planet.

All the Linux community wants is to create a really good, fully-featured, free operating system. If that results in Linux becoming a hugely popular OS, then that’s great. If that results in Linux having the most intuitive, user-friendly interface ever created, then that’s great. If that results in Linux becoming the basis of a multi-billion dollar industry, then that’s great.

It’s great, but it’s not the point. The point is to make Linux the best OS that the community is capable of making. Not for other people: For itself. The oh-so-common threats of “Linux will never take over the desktop unless it does such-and-such” are simply irrelevant: The Linux community isn’t trying to take over the desktop. They really don’t care if it gets good enough to make it onto your desktop, so long as it stays good enough to remain on theirs. The highly-vocal MS-haters, pro-Linux zealots, and money-making FOSS purveyors might be loud, but they’re still minorities.

That’s what the Linux community wants: an OS that can be installed by whoever really wants it. So if you’re considering switching to Linux, first ask yourself what you really want.

If you want an OS that doesn’t chauffeur you around, but hands you the keys, puts you in the driver’s seat, and expects you to know what to do: Get Linux. You’ll have to devote some time to learning how to use it, but once you’ve done so, you’ll have an OS that you can make sit up and dance.

If you really just want Windows without the malware and security issues: Read up on good security practices; install a good firewall, malware-detector, and anti-virus; replace IE with a more secure browser; and keep yourself up-to-date with security updates. There are people out there (myself included) who’ve used Windows since 3.1 days right through to XP without ever being infected with a virus or malware: you can do it too. Don’t get Linux: It will fail miserably at being what you want it to be.

If you really want the security and performance of a Unix-based OS but with a customer-focussed attitude and an world-renowned interface: Buy an Apple Mac. OS X is great. But don’t get Linux: It will not do what you want it to do.

It’s not just about “Why should I want Linux?”. It’s also about “Why should Linux want me?”

Ottobre 4th, 2009 at 3:58 pm

Questa è una traduzione all’Italiano di Stefano Chizzolini relativa ad un articolo di Dominic Humphries il cui originale non è più disponibile all’URL originale (http://linux.oneandoneis2.org/LNW.htm) poiché è stato rimpiazzato da un “remix”.

Vi avviso che le frasi racchiuse tra parentesi quadre (“[” e “]”) sono mie delucidazioni o commenti che non appartengono al testo originale.

Buona lettura!

PS: Vorrei segnalarvi un video molto simpatico (da diffondere!) che introduce i neofiti al mondo del Software Libero raccontando di Ubuntu (GNU/Linux): “Lo gnu, il pinguino e il cerbiatto esuberante” di Christian Biasco e Francesca Terri.

Nel seguente articolo, mi riferisco al sistema operativo GNU/Linux e a vari progetti FOSS [Free and Open Source Software: software a sorgente libera e software a sorgente aperta, NdT] sotto il denominativo comune di “Linux”. Solo per brevità…

Linux != Windows

(Linux non è Windows)

Se, come faccio io, anche voi dedicate del tempo a qualche forum su Linux, finirete inevitabilmente per montare su tutte le furie, come è capitato a me, a causa della mole di messaggi con questo tono:

“Salve! Sto usando Linux da qualche giorno, ed è in gran parte entusiasmante. Tuttavia, è un peccato che (questo o quello) non funzioni al modo di Windows. Perché mai gli sviluppatori non lo riscrivono completamente per farlo comportare come Windows? Sono certo che così Linux conquisterebbe molti più utenti!”

Potreste addirittura esservi scomodati a rispondere a queste richieste, solo per essere aspramente controbattuti da un novellino di Linux che dà per scontato che la sua idea, basata su anni di esperienza con un sistema operativo diverso più qualche ora su Linux, sia rivoluzionariamente brillante, e a voi non piace perché siete un “utente Linux della vecchia scuola” che considera le interfacce grafiche opera di Belzebù e vorrebbe che tutti fossero costretti ad inchiodarsi alla riga comandi.

Questo articolo intende spiegare a quei novellini esattamente perché le loro idee tendono ad essere flammate piuttosto che accettate.

Primo fra tutti, l’argomento più gettonato: “Se Linux lo facesse, molta più gente gli si convertirebbe da Windows!”

Allora, consentitemi di spiegare qualcosa che è fondamentale per capire Linux: la comunità di Linux non sta tentando di fornire all’utente Windows medio un sistema operativo sostitutivo. Lo scopo di Linux non è “Linux su ogni desktop”.

Davvero. Onestamente, non lo è. Certo, sono entrambi sistemi operativi. Certo, possono essere entrambi usati per le stesse cose. Ma questo fa di Linux un’alternativa, non un rimpiazzo. Potrebbe sembrare una distinzione insignificante, ma in effetti è di vitale importanza.

Linux Windows è come Motociclette Automobili: entrambi sono veicoli che vi portano da A a B attraverso le strade. Ma hanno forme diverse, dimensioni diverse, controlli diversi e funzionano in maniere fondamentalmente diverse. Non sono liberamente intercambiabili. Hanno utilizzi diversi e diversi punti di forza & debolezza, e dovreste scegliere quello più appropriato, non sceglierne uno e aspettarvi che faccia tutto quello che fa l’altro.

A un automobilista potrebbe capitare di restare imbottigliato nel traffico e vedere una moto sfilargli al fianco indisturbata. Egli potrebbe invidiare la capacità del motociclista d’ignorare agevolmente quello che per un’auto è un noioso problema. Se quell’automobilista poi dicesse “So tutto delle automobili, quindi so già tutto delle motociclette!” allora sbaglierebbe.

* Se quell’automobilista comprasse una moto e poi scoprisse che l’acceleratore è una manopola invece che un pedale, potrebbe lamentare che le moto debbano essere munite di un pedale per dare gas.

* Se quell’automobilista avesse una moglie e due figli, potrebbe considerare un difetto la capacità delle moto di ospitare un singolo passeggero. Egli potrebbe suggerire che le moto siano riprogettate per trasportare quattro persone, in doppia fila.

* Se quell’automobilista provasse a partire, accorgendosi poi di essere caduto perché non è abituato a mantenersi in equilibrio, potrebbe suggerire che le moto debbano essere riprogettate a quattro ruote.

* Se l’automobilista notasse che piega in curva, potrebbe suggerire che le moto debbano essere munite di stabilizzatori per tenerle dritte quando affrontano le curve.

* Se l’automobilista volesse evitare che gli venga rubata la moto, potrebbe lamentare che non ci siano portiere per tenere fuori potenziali ladri, rendendo la sua moto più a rischio di furto rispetto a un’auto.

* Se l’automobilista trovasse che il casco gli è d’impedimento, potrebbe suggerire che si inserisca un airbag nel manubrio della moto in alternativa al fastidioso casco.

E in ogni caso, egli sbaglierebbe. Perché pensa che una motocicletta sostituisca un’automobile, che possa e debba fare tutto quello che un’auto sa fare. Che possa funzionare allo stesso modo di un’auto, e che le caratteristiche “mancanti” di un’auto possano esserle direttamente appiccicate sopra.

Alla stessa stregua, solerti novizi di Linux suggeriscono che Linux debba somigliare di più a ciò cui loro sono abituati. E si piantano, per tutte le medesime ragioni. Linux e Windows si potrebbero usare per le stesse finalità, né più né meno di un’automobile e una motocicletta. Ciò non vuol dire che si possa passare direttamente dall’una all’altra, né tantomeno che le caratteristiche possano o debbano scambiarsi direttamente dall’uno all’altro.

Troppa gente pensa che migrare da Windows a Linux è come saltare da una BMW a una Mercedes [sarebbe più appropriato il viceversa, NdT ;-)]. Pensano che i controlli debbano essere gli stessi, la loro esperienza debba trasferirsi indenne, e tutte le differenze debbano essere in larga parte cosmetiche. Pensano che “Mi serve un’auto per usare la strada, mi serve un sistema operativo per usare il computer. Le auto funzionano tutte allo stesso modo, così i sistemi operativi dovrebbero funzionare tutti allo stesso modo.” Ma questo è inesatto. “Mi serve un veicolo per usare la strada, mi serve un sistema operativo per usare il computer. So come guidare l’auto, ma sono ignorante di moto. So come usare Windows, ma sono ignorante di Linux.” – questo è esatto.

Un utente Windows deve capire che lui è un utente esperto solo di Windows, non un utente esperto di computer; proprio come un automobilista è solo un conducente di automobili, non un conducente di veicoli polivalenti. Un utente Windows su Linux deve capire che è appena tornato ad essere novizio, proprio come un automobilista su una motocicletta. Un utente Windows deve accettare che ci siano modi diversi per raggiungere il medesimo risultato, così come un automobilista deve abituarsi al manubrio al posto del volante e alla necessità del casco che mai ebbe prima. E deve prepararsi ad accettare che “differente” non significa “inferiore”.

Questa semplice constatazione causa gravi difficoltà agli utenti Windows più scafati. Arrivano a Linux con tanti comportamenti consolidati e l’attitudine dell'”Io so esattamente come usare un computer, grazie tante.” Il problema è che… non lo sanno! Sanno solo come usare Windows. Quando capitano su un diverso sistema operativo, questi “power users” [utenti sofisticati, NdT] sono quelli con i problemi peggiori: hanno molto di più da disimparare.

Laddove un novellino dice “Io non so” e inizia a esplorare o chiedere sui forum, il Windows Power User dice “Io so come si fa, faccio così, così, cosà, e poi… non funzia! Stupido sistema operativo!” E quindi “Se a me che sono esperto non riesce di farlo camminare, un novellino è senza speranza! Linux non è in alcun modo pronto per l’uso desktop!”. Non si accorgono che tutta la loro conoscenza gli rema contro, provocandogli più problemi che a utenti meno esperti. Hanno fatto l’errore di pensare che Linux sia un software differente che fa la stessa cosa di Windows, mentre è effettivamente software differente che fa cose differenti. Non sta facendo un cattivo lavoro sulle stesse operazioni, sta facendo un buon lavoro su operazioni alternative.

Linux è un’alternativa a Windows, ma non un rimpiazzo. Non sarà mai un rimpiazzo, perché ha obiettivi incompatibili. L’obiettivo di Microsoft è di piazzare il proprio software su quanti PC possibile, dato che la sua priorità è il profitto. Linux non ha quest’obiettivo, perché Linux è gratuito [il termine inglese “free” equivoca felicemente con il significato di “libero”, NdT]. Ha una priorità differente.

Comprendere questo è comprendere il FOSS [“software a sorgente libero/aperto”, NdT]. E’ perfettamente comprensibile che i novellini di Linux non lo capiscano ancora – sono nuovi al concetto. Sono abituati a pensare in termini di software proprietario. Allora lasciatemelo spiegare:

Il tipico software FOSS è creato da qualcuno che si guarda attorno, non trova alcun software preesistente che gli piaccia, e così ne scrive uno proprio. Poi, dato che lui è un così bravo ragazzo, dischiude il codice sorgente e dice al mondo “e ora a voi!”. Lo può fare perché costa nulla duplicare il software, e a lui non costa di più darlo al mondo piuttosto che tenerselo. Non soffre a cederlo.

Comunque, la cosa importante da ricordare è: egli non trae nemmeno beneficio dal cedere il suo software. Che venga usato da una persona, o da un miliardo, non fa differenza allo sviluppatore. Oh, sicuro, si prende la soddisfazione di sapere che ha fatto un prodotto popolare: il numero di persone che lo usano può essere un valido sprone individuale; un modo, se volete, di tenere il punteggio. Ma non gliene viene un baiocco: è FOSS.

Se il software ha successo, altra gente se ne interesserà, e aiuterà a migliorarlo. Questo è il vantaggio principale del FOSS: ogni utente è un potenziale sviluppatore. Ciascuno può introdursi e fare la propria parte per far funzionare il software meglio, con più funzioni, e meno difettoso. E’ splendido quando un pezzo software attrae una comunità di sviluppatori. Ma è splendido per il software. Rende il software migliore. Non rende lo sviluppatore più ricco. Gli richiede solo più del suo tempo.

Il FOSS è l’esatto opposto del software proprietario alla Windows: nel FOSS l’obiettivo è il software, non il numero di utenti finali. Il software che funziona a dovere ma ha solo una manciata di utenti è considerato un fallimento secondo gli standard del software commerciale, ma un successo secondo gli standard FOSS.

Fare FOSS significa fare software di buona qualità, software che sa FARE le cose. Se lo volete usare, ci si aspetta che investiate tempo per apprendere come usarlo. E’ stato creato e fornito a voi, gratis, da gente che ha investito parecchio del proprio tempo su di esso senza lucro personale. Il meno che possiate fare per ripagare il loro contributo è investire un po’ del vostro tempo prima di lamentarvi che non funziona al modo dell’equivalente software Windows.

“Aha, ora ti frego,” dice il novellino compiaciuto. “Ci sono progetti Linux che mirano a sostituire Windows, non solo esserne un’alternativa.”

E’ facile vedere da dove venga quest’idea. KDE e Gnome, ad esempio, forniscono un ambiente desktop che è molto più simile a Windows dei tipici gestori di finestre e righe comandi Linux. Linspire è una distribuzione basata quasi interamente sull’idea di rendere Linux simile a Windows.

Tuttavia, paradossalmente, questi provano la mia asserzione meglio di quella del novellino.

Perché? Perché questi progetti sono normali progetti FOSS, interamente gravitanti attorno al principio di migliorare il software. La sola differenza è che una delle definizioni di qualità in questi progetti è “Quanto agevolmente può usarlo un utente Windows?”

Non appena lo interiorizzate, non potete far altro che convenire che questi progetti sono 100% tipicamente Linux, con il solo scopo di migliorare il software. Questi sono progetti fatti da sviluppatori Linux ancor più altruisti del solito: non fanno software per il loro proprio uso, visto che conoscono Linux molto bene. Invece, fanno software interamente per il beneficio di altri: software che rende la transizione da Windows a Linux più semplice.

Questi sviluppatori, consci che ci sono utenti Windows desiderosi di migrare a Linux, hanno messo un sacco d’impegno per creare un ambiente Linux che gli utenti Windows possano trovare confortevolmente familiare. Ma non hanno fatto ciò per tentare di sostituire Windows, sebbene il risultato finale possa dare questa impressione. E’ l’obiettivo finale a fare la differenza: l’obiettivo non è fare un rimpiazzo di Windows; l’obiettivo è facilitare la transizione di un utente Windows verso Linux.

Non è inusuale osservare ostilità verso questi progetti. Talvolta per motivi razionali, comprensibili (“KDE è un divoratore di risorse, usa Fluxbox”), talaltra per atteggiamenti irrazionali, ostili (“il software simile a Windows è cattivo”). Questo non è, effettivamente, un atteggiamento anti-Microsoft o anti-Windows. Invece, è la molto più semplice avversione verso ciò che non si comprende.

Il “tipico” utente Linux è un appassionato: usa i computer perché i computer sono divertenti, programmare è divertente, sfrucugliare/smanettare/pistolare è divertente. E Linux è un sistema operativo assai migliore per l’appassionato smanettone: può smontarlo fino al livello più fondamentale, e riassemblarlo esattamente come gli pare.

Tuttavia, il flusso attuale di nuovi utenti Linux è in larga parte costituito da non-appassionati non-smanettoni. Vogliono solo che il computer funzioni, un computer che funzioni come Windows. Non gliene importa di spendere del tempo settando Linux per farlo girare come li aggrada, vogliono che funzioni subito così, bell’e pronto.

Ed è perfettamente giusto, ma dalla prospettiva di un tipico utente Linux, questo è come la pretesa di chi vuole un’automobile Lego già preassemblata e tutta incollata in modo tale da non potersi scomporre. E’ alieno alla loro comprensione. L’unico modo con cui possono reagire è con uno sconcertato “Perché mai qualcuno vuole quello?”

E’ sconcertante. Se vuoi un’automodello già pronto, compra un’auto giocattolo. Se vuoi un’auto che puoi costruire e scomporre, compra Lego. Perché mai qualcuno vuole un’auto Lego per usarla come un’auto giocattolo? Il punto fondamentale di Lego è che ti diverti ad assemblarla da te!

Ecco come un tipico utente Linux reagisce alla brigata del “Perché non può solo funzionare?”: “Se vuoi solo che funzioni, usa Windows. Se vuoi smanettarci, usa Linux. Perché mai vuoi passare a Linux se non hai alcun interesse a trarre vantaggio dalla sua natura open source [“a codice sorgente aperto”, NdT]?”

La risposta, solitamente, è che loro non vogliono effettivamente passare a Linux. Vogliono solo fuggire da Windows: stanno scappando dai virus; si stanno mettendo in salvo dal malware; tentano di disfarsi delle restrizioni all’uso dei loro software a pagamento; stanno tentando di sgusciare dalle grinfie dell’EULA [“accordo di licenza utente finale”, NdT]. Non stanno cercando di entrare in Linux, stanno cercando di uscire da Windows. Linux è semplicemente la meglio conosciuta alternativa.

Qualcosa di più tra poco…

Potreste pensare “OK, questo spiega perché gli sviluppatori non fanno uno sforzo deliberato per far funzionare il loro software come Windows. Ma certamente al software Linux si potrebbe dare un’interfaccia grafica [“Graphical User Interface” (GUI), NdT] che sia amichevole come Windows senza per questo interferire con i principi FOSS?”

Ci sono alcune ragioni per cui questo non è il caso.

Primo: Pensate veramente che chi crea un pezzo software gli dia deliberatamente un’interfaccia utente miserabile?

Quando qualcuno devolve una larga porzione del proprio tempo alla creazione di un pezzo software, egli farà l’interfaccia utente [“User Interface” (UI), NdT] migliore possibile. La UI è parte molto importante del software: è inutile avere funzionalità se non vi si può accedere attraverso l’UI. Può darsi che non sappiate quale sia, ma c’è sempre un motivo per cui l’UI funziona nel modo in cui funziona. Perché? Perché è la migliore UI che l’autore potesse creare.

Prima d’insistere che una UI tipo Windows renderebbe il software migliore, tenete a mente questo fatto: L’autore di questo software, un codificatore che, per definizione, conosce molto più di voi questo pezzo software, non concorda con voi. Può darsi che si sbagli, ma spesso è il contrario.

Secondo: SONO già disponibili interfacce grafiche carine e simil-Windows. Non mi riesce di ricordare una funzione che non si possa controllare attraverso una GUI, non importa quanto di alto livello. Potete compilare il vostro kernel (make xconfig), settare il vostro firewall (fwbuilder), partizionare il vostro hard drive (qtparted)… è tutto lì, bello, interattivo, intuitivo, e amichevole.

Ma il “ciclo di rilascio” di Linux non è quello di Windows. Non vi rilasciano un rifinito, lucidissimo pacchetto GUI sin dagl’inizi. Le GUI aggiungono complessità senza funzionalità al software. Uno sviluppatore non si siede per progettare una bella GUI che fa niente, egli si siede e crea un pezzo software che fa ciò che gli serve.

La prima cosa che un pezzo software fa è essere usabile dalla riga comandi [“Command Line Interface” (CLI), NdT]. Avrà probabilmente ogni sorta d’opzioni d’invocazione, e forse un prolisso file di configurazione. Questo è come inizia, perché è la funzionalità ciò che è richiesto. Tutto il resto viene in seguito. E pure quando il software ha una GUI carina, è importante ricordare che di solito esso può ancora essere controllato completamente dalla CLI e dal file di configurazione.

* Questo perché la CLI ha molti vantaggi: la CLI è universale. Ogni sistema Linux ha una CLI. Ogni eseguibile può essere lanciato dalla CLI. E’ facile comandare il software remotamente attraverso la CLI.

Niente di ciò è vero per la GUI: alcune macchine Linux non hanno il sistema di finestratura X11 installato; qualche software non ha GUI; qualche software non è disponibile dai menu GUI; spesso non è facile o pratico usare uno strumento GUI remotamente

Per concludere, molteplici GUI possono esistere per svolgere lo stesso compito, e non si può prevedere quale sia installata.

Quindi ricordate, se chiedete “Come faccio…?”, vi sarà molto probabilmente detto come farlo attraverso la CLI. Ciò non significa che può solo essere fatto dalla CLI. Riflette appena l’importanza relativa che la GUI ha comparata alla CLI nello sviluppo di un progetto software.

* Windows è totalmente centrato sulla GUI. E’ un sistema operativo basato sulla GUI con una misera (ma in corso di miglioramento) CLI. Non c’è praticamente software Windows senza GUI. Questo tende a far credere alla gente che la GUI sia parte vitale e integrale del software. Ma in Linux, il software viene rilasciato allorché è funzionale. Solo dopo che è diventato stabile, ragionevolmente ripulito dai bachi, e ricco di funzioni, diventa conveniente aggiungergli una GUI.

Provate a pensare al software senza un’utile GUI come un'”anteprima furtiva” piuttosto che un prodotto finito. Il FOSS è molto raramente “finito”, è in continuo perfezionamento. Al momento opportuno, sarà reso amichevole. Ma prima, è più importante farlo funzionare meglio piuttosto che farlo sembrare migliore. Siate contenti che abbiate avuto la funzionalità molto prima di tutti gli applicativi Windows che hanno bisogno di una buona GUI, invece di chiedere oggi il software di domani. Il FOSS è più un viaggio che una destinazione.

L’ultima cosa che dovete fissarvi in testa: le GUI per il software saranno spesso un pezzo software separato. Potrebbe anche darsi che sia stato sviluppato in maniera completamente indipendente dal software originario, da sviluppatori completamente diversi. Se vuoi una GUI, non è improbabile che questa sia un’installazione separata, piuttosto che un pezzo unico.

Questo, indubbiamente, significa un passaggio ulteriore per ottenere quella GUI dal comportamento elusivo, “alla Windows”, ma ciò non toglie che così potete fare proprio tutto quello che volete attraverso una bella GUI, “proprio come Windows”. Avete solo da ricordare: una GUI è solitamente l’ULTIMO passaggio, e non il primo. Linux non privilegia la forma alla sostanza.

Terzo: Linux è deliberatamente progettato per l’utente informato e consapevole, piuttosto che il principiante ignorante. Questo per due ragioni:

* L’ignoranza sarà pure beata, ma dura poco. La conoscenza è eterna. Potrà necessitare giorni, settimane o mesi per portare il vostro livello conoscitivo da “novellino di Linux” a “utente medio di Linux”, ma una volta che c’è, avrete anni di utilizzo di Linux di fronte a voi.

Ficcare codice in quantità per rendere il software più semplice ai nuovi venuti sarebbe come piazzare permanentemente ruotine d’equilibrio su tutte le biciclette. Potrebbero rendere più facile l’inizio, ma poi…?

Non vi comprereste una bicicletta con le ruotine adesso, ne sono certo. E non perché voi siate dei freakettoni contrari all’amichevolezza. No, sarebbe perché sono inutili per voi, e inutili a chiunque non sia principiante, e tutto quello che farebbero sarebbe impacciarvi.

* Non conta quanto sia buono il software in sé, esso è buono quanto il suo utilizzatore. La porta più sicura al mondo non è di ostacolo ai ladri se si lasciano la finestra spalancata, la porta non chiusa, o le chiavi nella toppa. Il motore a benzina più efficiente al mondo non andrebbe granché lontano se lo riempiste di diesel invece che benzina.

Linux consegna tutto il potere nelle mani dell’utente. Ciò include il potere di scassarlo. Il solo modo di mantenere Linux ben funzionante è di imparare quel tanto che basta per sapere cosa si sta facendo. Facilitare all’utente il paciugamento di funzionalità che non capisce non farà altro che rendere più probabile per lui rompere qualcosa per sbaglio.

Quarto: Dove, nel testo precedente, avete scorto un modo con cui il FOSS beneficerebbe effettivamente dall’attrarre caterve di tipici utenti Windows?

Prendetevi del tempo. Rileggetelo, se volete. Aspetterò.

Il principio-guida di Linux e del FOSS è “fai buon software”. Non è “fai software di rimpiazzo a Windows”. La sola cosa con cui un’orda di tipici utenti Windows contribuirà a Linux sono le lamentele. Di che si lamenteranno? “Non funzia come qua su Windows.”

No, non lo fa. Se funzionasse come Windows, Linux s’attaccherebbe al tram. Sarebbe una bruttacopia che nessuno userebbe. La ragione per cui la gente è così appassionatamente devota a Linux è che non funziona come Windows. Non fa tutto per voi, non presuppone che voi siate eterni pivelli ignoranti, non vi nasconde tutti i meccanismi interni.

Windows vi scarrozza in giro; Linux vi dà le chiavi e vi fa sistemare al posto di guida. Se non sapete guidare, il problema è vostro. E vostra è la colpa. Una marea di gente vi aiuterà a imparare se lo chiedete. Ma non avrete successo se tentate di convincere qualcuno che ciò di cui Linux ha bisogno è uno chauffeur.

“Ma questo renderebbe Linux così tanto più popolare!”, il lattante strepita.

Può anche darsi. Ma quanti sviluppatori Linux beneficerebbero da un Linux popolare? Linux è gratuito, come può esserlo la birra a scrocco. Nessuno tra quelli che creano Linux profitta dall’acquisizione di una più larga base di utenti. Nessuno tra quelli nei forum di Linux profitta dall’acquisizione di una più larga base di utenti. La finalità di Linux non è “acquisisci una più larga base di utenti” – quella è la finalità del software proprietario.

L’obiettivo di Linux è fare un sistema operativo davvero pregevole. Gli sviluppatori sono occupati ad aggiungere funzionalità, rimuovere bachi, e migliorare le implementazioni esistenti. Non sono impegnati a piantare cartelloni pubblicitari che decantano quanto è bella la loro roba. Questo dovrebbe dirvi qualcosa su dove stiano le loro priorità.

E guardate a ciò che quest’approccio ha comportato alla base degli utenti Linux: l’ha fatta aumentare. Linux è partito piccino, e si è ingigantito. La ragione per cui ha attratto così ampi consensi? Perché ha puntato sempre sulla qualità. Gli utenti attratti da Linux sono utenti che vogliono la libertà e la qualità che solo il FOSS può dare loro. Linux è diventato grande perché non si è mai interessato di quanto grande fosse diventato. Gli sviluppatori si sono focalizzati esclusivamente sul farlo funzionare, e funzionar bene, e così hanno attratto utenti che volevano un sistema operativo che funzionasse, e pure bene.

Buttar via improvvisamente tutto e focalizzarsi invece sul rendere Linux il rimpiazzo di Windows sarebbe uccidere proprio quella cosa che ha reso Linux quello che è. Ci sono aziende là fuori che hanno osservato la crescita di Linux, e vogliono farci i quattrini sopra. Sono frustrate dalla GPL [“General Public License”, licenza GNU del software libero, NdT], che rende molto difficile per loro vendere Linux ai prezzi Microsoft. “Linux morirà se resterà aperto”, dicono, “poiché nessuno riesce a farci sopra i soldi.”

Non si accorgono che rendere Linux proprietario sarebbe ammazzare la gallina dalle uova d’oro. Linux è cresciuto perché è FOSS, e nessuno intendeva farne il sostituto di Windows. Linux prospera perché combatte Windows su un fronte nel quale Microsoft non potrà mai sconfiggerlo: apertura e qualità.

Per molti utenti Windows, Linux è una bruttacopia di Windows. Ha apparentemente meno funzionalità, meno integrazione, e molta più complessità. Da quel tipo di utenti, Linux è visto come un cattivo sistema operativo. E d’altronde correttamente: esso non soddisfa le loro esigenze. Le loro esigenze sono un sistema operativo che è semplicissimo da usare e fa tutto senza che abbiano a imparare alcunché.

Windows è creato per utenti non tecnici. La percezione diffusa tra quegli utenti è che Linux è difficile da usare. Non è così, ma è un pregiudizio comprensibile.

Linux è effettivamente beatamente semplice da usare. Genuinamente. E’ davvero semplice. La ragione per cui non è percepito in questo modo? Perché il termine “facilità d’uso” è stato vergognosamente distorto. Nell’uso comune, “facile da usare” ora significa “facile per fare qualcosa senza sapere prima come farla” [mi viene in mente l’innocente candore con cui un neonato espleta i suoi bisogni corporali — ma siamo cresciuti, ragazzi: è l’ora di pretendere da sé stessi qualcosa di più che pappa-cacca-nanna!, NdT]. Ma quello non è assolutamente “facile da usare”, o no? Quello è “facile da intuire”. E’ come la differenza tra:

* una cassaforte con un’annotazione su di essa che recita “Sbloccare la cassaforte girando la ghiera a 32 poi 64 poi 18 poi 9, poi girare la chiave e sollevare la maniglia”

e

* un’auto che può essere aperta premendo il tasto “apri” sul telecomando.

E’ molto più facile aprire l’auto, giusto? Un tasto da ovunque vicino l’auto, opposto a numerosi giri di ghiera molto specifici. Tuttavia, per qualcuno che non sa come aprire ambedue è più facile aprire la cassaforte che l’auto: la cassaforte ha istruzioni chiare disponibili in loco, mentre l’auto ha appena i tasti che manco sono applicati all’auto.

Linux è lo stesso. E’ facile da usare se sapete come usarlo. E’ facile da usare, ma non è sempre facile da imparare. Solo se avete la volontà di investire del tempo per imparare Linux lo troverete semplice. Inevitabilmente, più si scompone un’operazione nei suoi semplici passaggi, più passaggi si devono compiere per eseguire l’operazione.

Come esempio davvero semplice, prendete questo esercizio arbitrario: volete spostare cinque linee (paragrafi) dal centro di un documento testuale alla fine.

In MS Word, MS WordPad, o MS Notepad, tutti editor di testo “amichevoli” di Windows, il modo più rapido per fare ciò è:

– Ctrl-Shift-Down

– Ctrl-Shift-Down

– Ctrl-Shift-Down

– Ctrl-Shift-Down

– Ctrl-Shift-Down

– Ctrl-X

– Ctrl-End

– Ctrl-V

(si assume che si stia usando la tastiera. Altrimenti, occorrerà qualche operazione di clicca-e-trascina col mouse e un’autoscorrimento affidabile).

In vi [pronuncia: “vi-ai”, NdT], invece, è:

– d5d

– Shift-g

– p

(o, se si conosce vi veramente bene, appena “:1,5m$” funziona altrettanto bene!)

Vi, che è “inamichevole” quasi quanto efficace, batte le offerte di Microsoft a mani basse. Perché? Perché vi fu progettato per la funzionalità, mentre Microsoft progetta per l'”amichevolezza”. Microsoft spezza tutto in piccoli passaggi, e così sono necessari molti più passaggi per ottenere la medesima operazione.

Questo rende vi molto più rapido e facile da usare per virtualmente tutte le operazioni di modifica testuale. Appena quanto voi sapete come usarlo. Se non sapete che “d5d” significa “Piazza cinque linee di testo nel buffer, ed eliminale dal documento” allora faticherete per far funzionare vi. Ma se lo SAPETE, allora volerete con esso.

Così quando qualche novellino nota quanto rapidamente e facilmente un utente esperto di vi sa fare le cose, immediatamente concorda che vi è superiore a Word per la modifica testuale. Allora tenta di usarlo lui stesso: lo fa partire e si trova di fronte a uno schermo pieno di “~”; quindi prova a digitare qualcosa, ma sullo schermo non compare nulla.

Scopre i modi d’inserimento e di comando, e inizia a provare l’uso di vi con un bagaglio limitato di conoscenza delle sue funzioni. Fatica, poiché ci sono così tante cose da imparare per riuscire a far funzionare vi come si deve. Allora lamenta “vi sarebbe molto meglio se fosse così facile da usare come Word!”

Ma il vero problema è “Io non so usare vi e non mi frega niente imparare.” Ma questo significherebbe che il problema era il suo, mentre invece egli incolpa dei propri problemi il software. Non importa se migliaia d’individui usano felicemente vi senza problemi: è troppo difficile da usare, deve essere cambiato!

E credetemi, se riuscirà a fare un editor testuale che è “amichevole” come Word e funzionale come vi, sarà accolto con nient’altro che applausi. In effetti, sarà probabilmente insignito del Premio Nobel per la Genialità, visto che nessun altro è mai stato in grado di farlo in precedenza. Ma belare ai quattro venti che vi è difficile da usare sarà accolto da derisione, perché il problema non è vi, il problema è lui.

Illustrazione PEBKAC da UserFriendly.org

Da UserFriendly.org Copyright © 2004 J.D. “Illiad” Frazer.

E’ come acquistare il pennello di da Vinci e poi lamentarsi che ancora non si è buoni a dipingere. Non fu il pennello a fare Monnalisa, fu la capacità dell’artista. Il pennello è uno strumento che si affida alla capacità dell’utilizzatore. Non c’è altro modo per acquisire quella capacità che esercitarsi [anche se neppure questo talvolta basta, ma si tratta di casi disperati… ;*), NdT].

Lo stesso con vi. Lo stesso con svariati pezzi software Linux che i nuovi utenti lamentano essere “troppo difficili” o “non abbastanza intuitivi”, che stiano parlando di un editor di testo, un gestore di pacchetti, o la riga comandi stessa.

Prima di iniziare a insistere che qualcosa in Linux ha bisogno di correzione, c’è un’importante domanda da chiedersi: “Gli utenti esperti hanno problemi con questo?”

Se la risposta è “No”, allora il problema è vostro. Se altra gente riesce ad usarlo profittevolmente, perché voi no? Avete dedicato il tempo per imparare come usarlo? O vi aspettate che basti dirgli “Vai” perché lavori per voi?

“Amichevole” e “funzionalità grezza” sono esclusive. Tutti quei bottoncini e menù a cascata che sono vitali per rendere un pezzo software semplice da usare sono solo ostacoli sulla strada dell’utente esperto. E’ la differenza tra navigare da A a B con mappa & bussola, e andare da A a B seguendo i segnali stradali: chiunque può arrivare seguendo i segnali, ma c’impiegherà il doppio di chi sa come andarci direttamente.

Map of routes

Se voglio incollare il valore di una formula in Excel, devo farlo attraverso i menù Edit->Paste Special->Paste Values. Io non voglio navigare attraverso tutti quei penosi “amichevoli” menù, sottomenù e finestre di dialogo. Io voglio solo che sia fatto. E, ad essere onesto, se riprogrammo i tasti funzione e registro qualche macro, posso far fare a Excel e Word molte cose alla sola pressione di un tasto.

Ma questo non è veramente amichevole, ‘n’è vero? Richiede ancora all’utente di investire un mucchio di tempo nel software. Linux vi richiede di dedicare del tempo all’apprendimento delle funzionalità esistenti. Il software”amichevole” vi impone di dedicare il tempo a creare la funzionalità.

Se questo è il modo che preferite, va bene, proseguite come vi pare. Ma non perdete mai di vista il fatto che la colpa è della vostra ignoranza e non del software. Tutto il software Linux è supremamente facile da usare, una volta che lo sappiate usare. Se non imparate, non sarà facile, e ciò non perché il software sia colpevole.

Ora, potreste incominciare a pensare che Linux abbia un problema caratteriale. Non vuole utenti, non intende rendere la vita facile ai suoi utenti… è solo per smanettoni snob!

Niente di più falso. Certo che Linux vuole utenti! E sicuramente non vuole fare cose difficili. All’opposto: il software difficile da usare è, per definizione, software cattivo.

Ma dovete capire, le sue definizioni possono essere diverse dalle vostre, e diverse dalla “tradizionale” mentalità del software proprietario.

Linux vuole utenti che vogliono Linux. E tutto quello che ciò comporta: il software libero, con codice sorgente aperto; l’abilità di sperimentare con il vostro software; la posizione di chi è al posto di guida, in pieno controllo.

Questo è ciò che Linux è, tutto ciò che lo riguarda. La gente migra a Linux perché è stufa di virus, di BSOD, di spyware. E’ comprensibile. Ma quella gente non vuole Linux. Vuole solo Windows senza i suoi difetti. Non vogliono davvero Linux. Così perché Linux dovrebbe voler loro?

Ma se provano Linux per sfuggire a virus e spyware, e poi decidono di appoggiare l’idea di un sistema operativo sotto il loro pieno controllo… è così che vogliono Linux per quello che è. Ed è così che Linux vuole loro.

Prima che voi decidiate di passare a Linux, chiedete a voi stessi “Perché voglio cambiare?”

Se la risposta è “Voglio un sistema operativo che dia tutto il potere nelle mani dell’utente e si aspetti che lui sappia come adoperarlo”: scegliete Linux. Avrete da investire una quantità sostanziosa di tempo e sforzo prima di fargli fare ciò che vi pare, ma alla fine sarete premiati da un computer che fa esattamente ciò che voi volete.

MA…

Se la risposta è “Voglio Windows senza i suoi problemi”: fate un’installazione pulita di Windows XP SP2; settate un buon firewall; installate un buon anti-virus; non usate mai IE per navigare sul web; aggiornatevi regolarmente; riavviate dopo ogni installazione software; e leggete delle buone pratiche di sicurezza. Per quanto mi riguarda ho usato Windows dalla 3.1 fino alla 95, 98, NT, e XP, e non ho mai avuto un virus, sofferto di spyware, o craccato. Windows può essere un sistema operativo stabile e sicuro, ma sta a voi mantenerlo a quel modo.

Se la vostra risposta è “Voglio un rimpiazzo di Windows senza i suoi problemi”: comprate un Apple Mac. Ho sentito cose meravigliose sul rilascio Tiger di OS X, e forniscono pure hardware d’aspetto gradevole. Vi costerà un nuovo computer [con OS X 86 per Intel e qualche aggiustamento di compatibilità si potrebbe anche riciclare il proprio PC, NdT], ma otterrete ciò che volete.

In entrambi i casi, non passate a Linux. Sarete delusi sia dal software che dalla comunità. Linux non è Windows.

Se avete dei commenti, buoni o cattivi, su quest’articolo, segnalatemeli o scriveteli sul mio blog.

Ottobre 4th, 2009 at 4:22 pm

Ammettetelo, è un subdolo tentativo per suggerire la migrazione di massa a MacOSX/Apple.

Ottobre 15th, 2009 at 2:39 pm

Mooolta acqua è passata sotto i ponti:

conviene fare un giro in rete, per esempio a

http://sens2.noblogs.org/

e per avere uno sguardo abbastanza ampio sulle distro linux a

http://distrowatch.com/

p.s. per quanto riguarda osx, nulla da eccepire, ma se si prende una distro BSD e si fa il confronto al boot, si troveranno gli stessi “reggenti”….c’è da pensarci un po’.